Despite the confounding, authoritarian governing (if one can call it “governing”) aggression by the Trump administration and its lackeys (in what once used to be known as the Republican Party) I have noticed a deep hunger among many Americans of all backgrounds to see our way out of this destructive mess we are in.

Many millions of Americans continue to have faith in the processes of a hobbled judicial system that is under attack from the MAGA army. They are making phone calls, writing letters and sending postcards to their elected representatives; they are showing up in officials’ offices to vocalize their deep concern for the neglectful and hateful executive orders being carried out by the DOGE team under the leadership of the unelected, miscreant, bigoted billionaire Elon Musk; and they are giving what they can of their far-fewer-dollars in campaign contributions in order to plug the nuclear bomb sized hole in American politics thanks to the corrosive and corrupting Citizens United, thanks to Chief Justice John Roberts and his distinctly anti-democratic allies on the United States Supreme Court.

We wait for decent leaders from both parties, men and women of principle, resolve, openness to compromise, committed to the common good and the courage to stand up to the brazen meanness, narcissism and unrestrained bigotry that pours forth from the head and bitter heart of President Trump each and every day.

We wait while our allies stand in shock and grave concern for the integrity of democratic alliances as we do at what has become of America so quickly, so easily, it now seems. A nation that once with deep pride and resolve fought back against totalitarian forces but now enables the strong man mentality while crushing the aspirations and hopes of the most humble and modest among us while doing everything in its power to cripple, if not destroy, any opposition.

This cannot be who we are.

I am not a political man in the strictest sense (meaning, I don’t currently hold office.) But insofar as religiosity, faith, and houses of worship are woven into the fabric of American civic life, one must grant that there are political ramifications for messages that emanate from our sacred spaces, inspired by our varied approaches to and interpretations of our sacred scripture.

Put differently, I don’t believe it’s necessary to give political sermons. Perhaps I once did earlier in my life of rabbinic service. But it’s less so now. As age creeps in, I lean more these days toward the wisdom of Shammai, an early 1st century BCE Jewish sage who taught, “Say little, do much.”

Learning and teaching resonate more for me with each passing day; sharing wisdom with those who would venture into the thorny thicket of political expediency feels like a better use of my time and energy. Public posturing and displays of moral certitude wedded to political activism rarely move the needle these days. And when they do, it’s generally but a precious few examples in a generation.

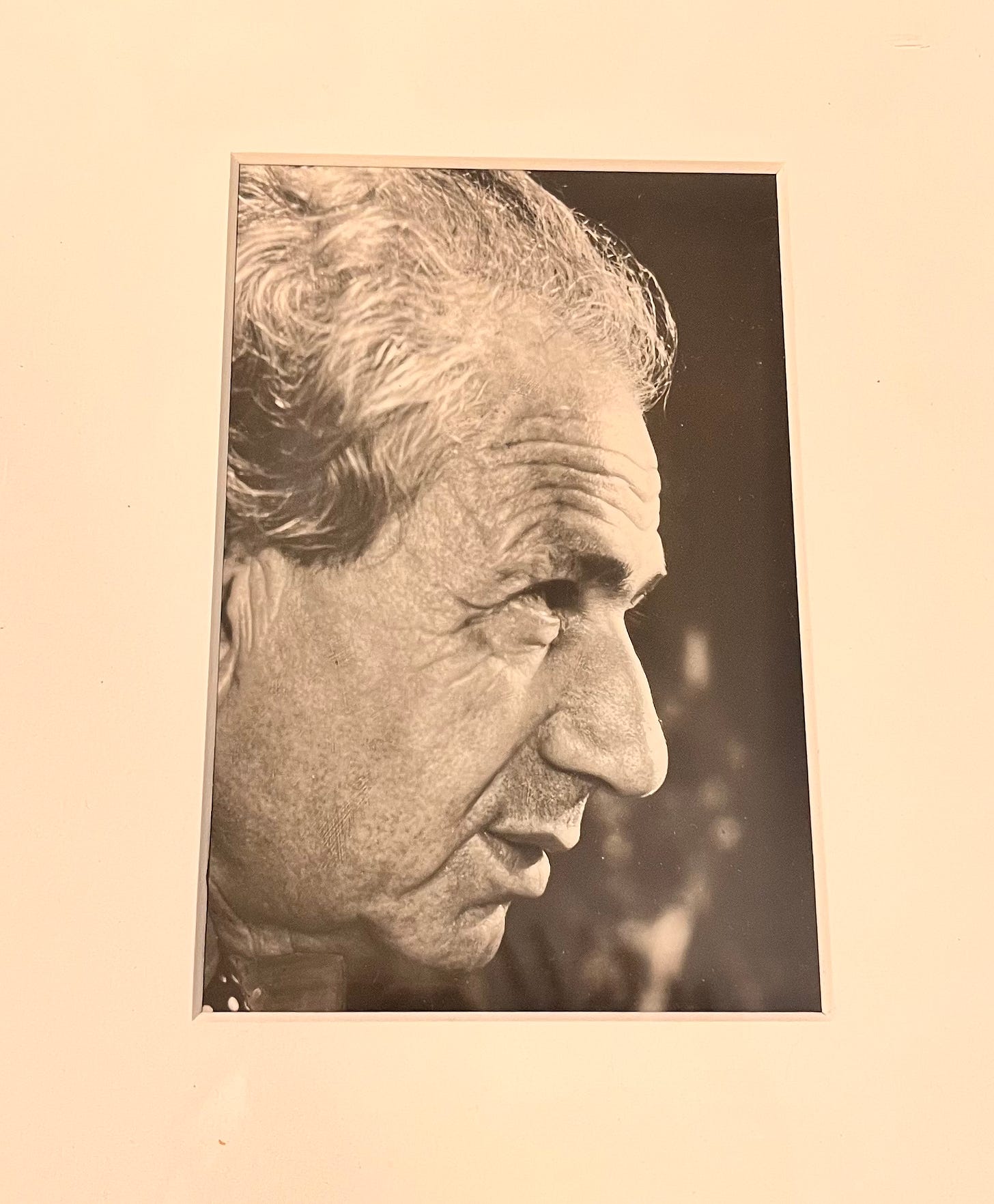

In my own study, I have upon my wall a portrait of Rabbi Joachim Prinz, who preached against Nazis from his Berlin pulpit until the Gestapo threatened his life once and for all and he escaped to Newark, New Jersey where he served a Jewish community there. Prinz looks out on my wall of books beside a portrait of Rev. Martin Luther King, who spoke truth to power as a Black American and paid the price for his prophetic leadership with his life – cut down in cold blood by an assassin’s bullet in Memphis, April 1968.

Little known to most, Prinz spoke just before King at the March on Washington in 1963, their speeches a kind of bookended argument for the power of scripture and spiritual narrative to redeem. Prinz spoke from his direct experience as a Jew with ancient roots in the Exodus narrative as well as his own contemporary reality as a German Jewish refugee from the Nazi regime. His wisdom was rooted in the Biblical creation story of God making all humans in the Divine Image and the Levitcal commandment to “love thy neighbor as thyself.”

Prinz said that day, “In the realm of the spirit, our fathers taught us thousands of years ago that when God created man, he created him as everybody's neighbor. Neighbor is not a geographic term. It is a moral concept. It means our collective responsibility for the preservation of man's dignity and integrity.”

Like a fearless Moses approaching Pharaoh in Egypt and demanding in the name of his God to “Let My people go,” Prinz decried the dangers of a passive citizenry that would tolerate bigotry and hatred in its midst. He did it once in Berlin under the Nazi regime and again in America amidst the brutality of racism, segregation, and violence against Black Americans seeking equality and justice under the law. “When I was the rabbi of the Jewish community in Berlin under the Hitler regime, I learned many things. The most important thing that I learned under those tragic circumstances was that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problem. The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence. A great people which had created a great civilization had become a nation of silent onlookers. They remained silent in the face of hate, in the face of brutality and in the face of mass murder. America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent. Not merely black America , but all of America . It must speak up and act,. from the President down to the humblest of us, and not for the sake of the Negro, not for the sake of the black community but for the sake of the image, the idea and the aspiration of America itself.”

For anyone familiar with the Hebrew Bible (my ur-text of sacred scripture) one knows that Moses confronting an evil, slave-holding Pharaoh; or the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah decrying corruption in the kings’ courts, the Temple and among the priesthood – “Is this not the fast I seek, to loose the fetters of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, give your bread to the hungry, house the poor, clothe the naked” – or even Abraham himself challenging God at Sodom and Gomorrah about the slaughter of innocents – “Shall the Judge of all the earth not do justice” – in these inspiring and sublime instances of confrontation, we find that a fearless, principled approach to moral action has political implications. Their light and determination shape societies, for the “idea and the aspiration” of what that society hopes to or positions itself to be.

In communities which are situated in deeply Republican strongholds where community leaders from politicians to the pulpit openly embrace the current MAGA zeitgeist, there is deep fear, even terror, in the most vulnerable populations. One response, of course, is to be active. To write letters, to demonstrate, to call our representatives. To show up. “Say little, do much.”

Another response, and one that has been particularly resonant for me, is to approach my neighbor with a look in the eye, with a warm hello, with the unreconstructed message that “you belong.”

When teaching publicly these past months since Trump’s election, I repeat to as many people who will listen this intergenerational conversation among sacred texts:

“You shall not hate your brother in your heart; you shall rebuke your fellow, and do not bear a sin because of him. You shall not take revenge, and you shall not bear grudge against the members of your people, you shall love your companion as yourself: I am God.” (Leviticus 19:17-18)

The sage Hillel said, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor, that is the entire Torah, the rest is just commentary, now go and study." (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a)

Rabbi Akiva said: “This is the great principle of the Torah: "You shall love your neighbor as yourself." (Genesis Rabbah 24:7)

These are and must remain the immovable pillars, drawn from the wisdom of our Jewish tradition, conveyed with urgency and love to our neighbors in this, our shared civil society. These are and must remain the idea and aspiration of America.

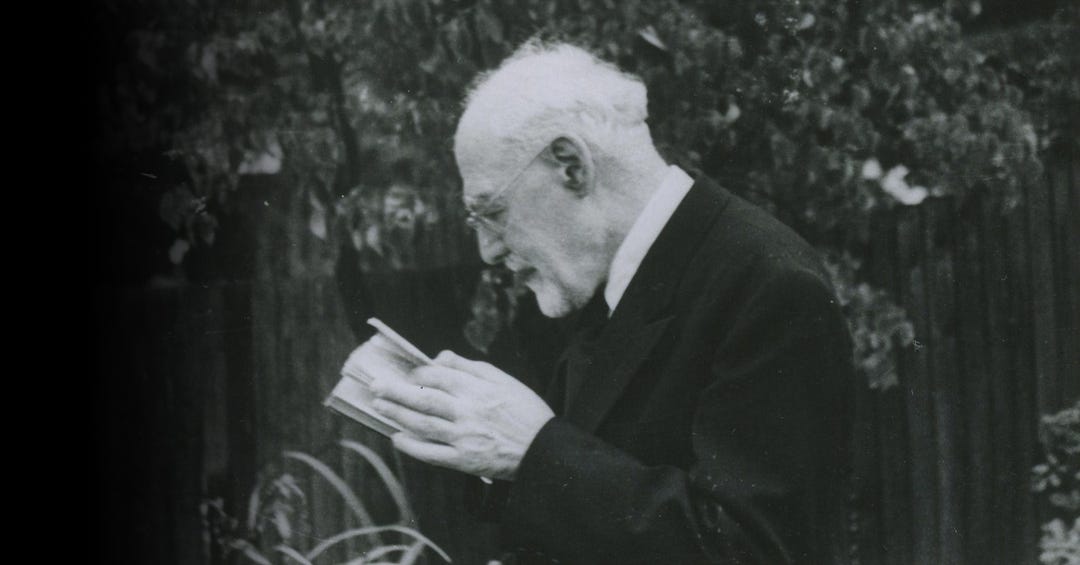

Some years ago I learned an unforgettable story about Rabbi Leo Baeck, another Berlin rabbi who continued to teach Judaism and take care of his congregants amidst the Nazi onslaught until he was deported to Theresienstadt. Baeck survived the war and moved to London, where he taught until he died in 1956. But one of the most remarkable things about Rabbi Baeck, among his many achievements, was that even after the war he returned to Germany to teach and encourage dialogue between Jews and non-Jews. To the very end, as a victim of indifference and hate, he modeled presence and understanding.

Rabbi Baeck’s students, according to this story (told to me by his granddaughter Marianne Baeck Dreyfus, of blessed memory) would often ask him, “Rabbi, the Germans are responsible for the Holocaust which killed 6 million of our people – how can you return there?” Baeck said, “On the day I was deported to Theresienstadt, a Christian neighbor risked her life by stepping out from a throng of neighbors to put bread in my pocket for the journey.”

The moral courage astonishes to this day and ought to serve us all as a reminder that the smallest acts can and must ultimately have the most redemptive results.

So thoughtfully written, so powerful. I hope people reading this will not remain silent. Max and I will be at the NYC rally on April 5th.

Beautifully said and perfect references from our rabbis long ago and more recent.