Bound Together by Love

One of the things I appreciate most about daily prayer is both its stable regularity coupled with the rare appearance of a new insight into what it is that I bind myself to each day.

A case in point is the following text, found in a series of set pieces to study each day as an expression of gratitude to God for giving us the Torah.

“Rabban Yohanan ben Zakai once was walking with his disciple Rabbi Joshua near Jerusalem after the Roman destruction of the Temple. Rabbi Joshua looked at the Temple ruins and said, “Oy, alas for us! The place which atoned for the sins of the people Israel through the ritual of animal sacrifice lies in ruins!” Then Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai spoke, “My son. Be not grieved. There is another way of gaining atonement even though the Temple is destroyed. We must now gain atonement through deeds of lovingkindness.” For it is written by the prophet Hosea, “Lovingkindness I desire, not sacrifice.”

This text is usually cited to indicate the evolution of Jewish thought in the wake of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem. While the exile of the Jewish people into the resulting diaspora that would frame Jewish history for two thousand years was an undeniable catastrophe, the rabbinic response was to build a new, post-Temple infrastructure of Jewish service. Torah learning, prayer, and deeds of lovingkindness would replace animal sacrifice, thereby ensuring that the Jewish people had a means by which to serve God, atone for sin, and build communities rooted in love and kindness.

The synagogue and house of study would serve as social, intellectual, and spiritual guarantors of Jewish survival wherever Jews lived. Even without a center, a nation, a capital, as it were, the people would not only survive but thrive. Centers of learning — from Jerusalem to Hebron; from the Galilee to Babylonia; from Egypt to Rome; and from Spain to Aleppo, Greece, Lithuania, Poland and on and on. Even with vast distances, violent disruptions and expulsions, the institutions of Jewish life held.

In some ways it was a miracle equal in significance to the parted waters of the Red Sea that ensured our delivery from Pharaoh’s pursuing army in Egypt. That the model has prevailed far longer than any Jewish kingdom lasted is a testimony to its brilliance and strength.

Yesterday, however, I read this text differently. Rather than read it as a witness to the Jews’ adaptive resilience, I plowed down into the personal, staying with the phrase that Yohanan utters to Joshua: “My son, be not grieved…there is lovingkindness which can replace sacrifice.”

בני אל ירע לך is even stronger in the Hebrew. I might translate it as, “My son, don’t do evil to yourself by remaining in grief,” focusing on the word, “ירע” whose root meaning echoes this way of reading. When we grieve overmuch, we damage ourselves in the process. In psychological terms, we call this “not being able to let go.” People see each other stuck in grief and advise: Let go of your anger; let go of your grief; or more to the point, let go of the self-pity. Yohanan says as much to Joshua, who only sees death and destruction in the burnt house of the Temple and therefore misses the embers that still burn for a rebuilding that is only denied or even repressed by a lack of imagination.

Substitute your self-pity for love, Yohanan tells his disciple. Move on. As someone who has been on the receiving end of that advice at various points in his life, as I’m certain many of you readers have been as well, it’s often the most difficult advice to follow. Not all of us are as hard-wired for fresh starts as Norman Lear famously is. The legendary writer, who is 102 years old, credits his longevity to his philosophy of life: “Over, next.” When one chapter ends, that its. Another begins. Oy, I wish it was that easy.

You might be interested to know that there is out there in the source material an alternative version of the text I just cited, where Yohanan says to Joshua “אל תירא לך” or “don’t be afraid.” In other words, there is another way of looking at this condition of not being able to move on and its rooted not in self-pity but in fear. In other words, change of any kind can be terrifying, even immobilizing to some.

I puzzled over the alternative readings yesterday and wanted to find one of the books which cited the above text. This led me to Boro Park in search of a rabbinic volume called Menorat HaMaor, the Illuminated Lamp, by Rabbi Isaac ben Abraham Aboab, a 14th century Spanish scholar. The work is often confused with another work by a different author from the same period whose name was Yisrael ben Yosef Alnaqua. The whole thing drew me in. I wanted to get my hands on this book. Whoever wrote it!

My first stop was at Seforim World on 16th Avenue. The seller was warm and apologetic. He made small humming noises over the phone as he searched. Alas, it would have to ordered from the warehouse. It would take a few days. So then I rode over to Eichlers on 13th Avenue but struck out there too.

But I still had fun. Because as a non-Hasidic, non-Orthodox person shopping for Jewish books in Boro Park, I suppose I could feel out of place. Between my bike helmet serving as a yarmulke and clean-shaven look, I do stand out. But a Jew in search of a book is a Jew in search of a book and for the more than 30 years that I have been going to these two booksellers, I am always heartened by the feeling of inclusion, respect, and love for learning that is shared when I show up in search of something. It’s just too easy these days to focus on our differences as Jews, on what divides us — whether it is approaches to worship, gender equality, levels of observance, relationship to Israel. I prefer, to quote Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, the love.

I loved seeing Haredi Jews not with iPhones but image-proof Nokias. I cherished the closeness of boys and girls huddled with one another (boys with boys, girls with girls) looking for books for school. My heart warmed at watching the undeniable closeness of this community and hearing them speak Yiddish — both as an expression of the language that has been the center of their world for a thousand years but also in defiance of Hitler, who sought to eradicate the Jewish people and the Jewish language in the Shoah. The embers of our cherished language, nearly wiped out by the Nazis, thrives. These young Jews still speak it; I haven’t a clue. I can pity myself for not knowing or being too lazy to find the time to learn it; or I can love them for keeping the flame alive. Yesterday, I chose love.

I didn’t find the exact book I was looking for but I found another application of the lesson that I learned in my prayer earlier that morning. You know, it’s easy for us Jews to criticize each other; to zero in on our differences. “They’re sexist. They’re right-wing. They won’t shake my hand!” But none of us is free of sin, isn’t that the point? In these communities, as insular or closed off as they may seem, there is also the deepest of commitments to family, to kindness, to charity, to language, to Torah, to love. I don’t choose to live there. I don’t think I could manage. I’m just not that committed in that way. One must admit that to oneself.

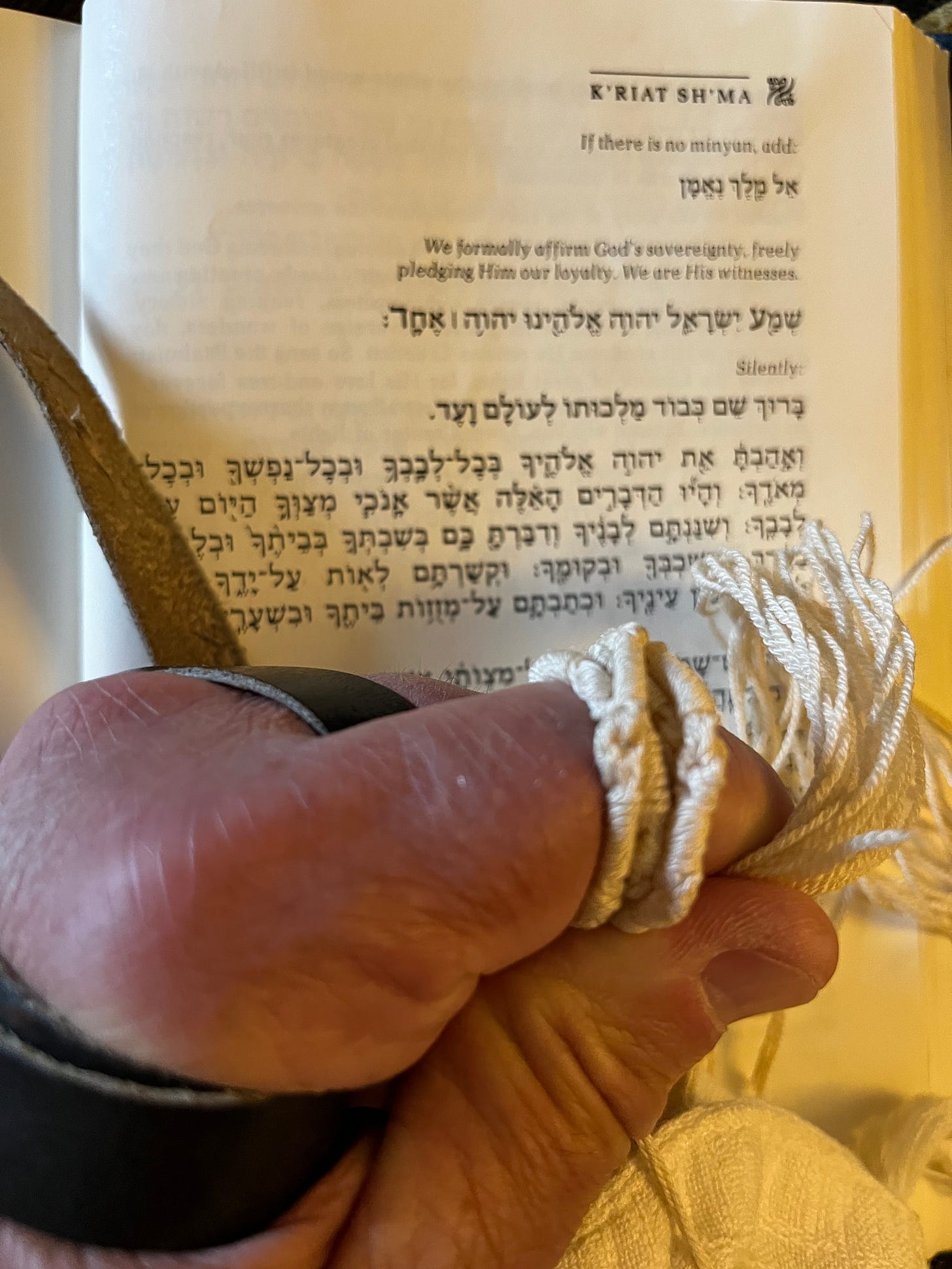

But when I visit for my books or bring together the four corners of the tzitzit on my prayer shawl, I am reminded that we are family — a complicated, complex family filled with limitless differences of expression and occasionally bound together by love.